What is Impressionism?

Impressionism, one of the most significant movements in art history, first emerged in painting before extending its influence to music and literature. It developed mainly in France during the late 19th century, flourishing between 1867 and 1886. A group of artists, united more by shared techniques than by a formal manifesto, sought to capture the fleeting effects of light and color in everyday life. Their work aimed to portray visual reality in a fresh, immediate way rather than through the polished finish of academic art.

The name Impressionism was not chosen by the artists themselves. It began as a term of mockery following the first group exhibition in Paris in 1874. Inspired by Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, critic Louis Leroy ridiculed the painting in his satirical review in Le Charivari, joking that it looked like nothing more than “a preliminary drawing for wallpaper.” Ironically, this insult gave the movement its lasting name.

Impression Sunrise, Claude Monet, 1872.

At the time, the Impressionists faced strong opposition from France’s conservative art institutions. Rejected by the official Salon, painters such as Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and Degas organized independent exhibitions to showcase their work. While critics often dismissed their paintings as rough or unfinished, progressive writers recognized their originality. In his 1876 essay La Nouvelle Peinture (The New Painting), Edmond Duranty praised their ability to depict modern life with an equally modern style, calling it a revolutionary break from tradition.

Although the artists did not initially embrace the label Impressionist, it eventually became a banner under which their work was celebrated. Today, Impressionism is remembered not only for its innovative style but also for its modern spirit—rejecting strict academic rules, embracing new technologies like portable paint tubes, and portraying contemporary life with vibrancy and immediacy.

What continues to define Impressionism for today’s audiences is both its subject matter and its technique. Bright, unmixed colors, visible brushstrokes, and outdoor painting (plein air) gave their works a freshness that captured fleeting moments in landscapes, city scenes, and everyday life. This approach transformed painting forever and left an enduring legacy in the broader world of art.

Impressionism: The First Modern Art Movement

Impressionism is often regarded as the first modern art movement, shaped by the sweeping changes of 19th-century France. The Industrial Revolution and the rise of the railroad gave Parisians new freedoms: affordable leisure time and the ability to escape the city for the countryside. Against this backdrop of modernization, a group of young artists began to rethink what painting could be.

Around 1860, Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Frédéric Bazille met while studying under the academic painter Charles Gleyre. Outside their formal training, the four friends boarded trains to the surrounding fields and riverbanks, where they painted directly from life. With their easels set up outdoors, they tried to capture sunlight glimmering on water, workers at their tasks, and Parisians enjoying leisure along the Seine.

This shift toward painting en plein air marked a radical break from tradition. Instead of polished, studio-bound compositions, these artists sought to convey fleeting impressions of light, movement, and modern life, qualities that would come to define Impressionism.

Characteristics and Style of Impressionism

There was no single, unified Impressionist style, but the artists of the movement shared several modern approaches to painting. By looking at these defining characteristics, you can better understand Impressionism and learn how to recognize it in artworks:

The Bold Brushwork and Loose Strokes

Impressionism is famous for its visible, textured brushstrokes. Artists used quick, loose marks to suggest movement, light, and immediacy rather than fine detail. This technique gave their paintings a sense of energy and spontaneity, as if the scene were captured in a fleeting instant. The canvas became a lively space where every stroke conveyed motion and atmosphere, blurring the line between reality and artistic expression.

Outdoor Painting (En Plein Air)

Many Impressionist artists preferred to paint outdoors in the countryside around Paris rather than remain confined to their studios. This practice, known as en plein air, became a defining feature of the movement and shaped its distinctive style. By working directly in nature, artists could capture the shifting effects of light, atmosphere, and fleeting moments with greater accuracy and immediacy.

Painting outdoors also encouraged speed and spontaneity, which translated into the loose brushwork and visible strokes characteristic of Impressionism. This approach allowed the artists to infuse their canvases with the genuine ambiance of the outdoors, creating scenes that feel fresh, vibrant, and alive to the viewer.

Emphasis on Light

Impressionism is synonymous with its focus on light, which transformed how artists perceived and represented the world. This attention to light became a defining theme of the movement, breaking away from traditional conventions and offering a new way of capturing reality.

Claude Monet’s series, such as Water Lilies, exemplify this approach. By studying how light shifted across water and landscapes at different times of day and in various seasons, Monet revealed the fleeting beauty of nature. His use of color and light created serene, evocative scenes that continue to resonate deeply with viewers.

Capture of Fleeting Moments

Impressionist artists sought to capture the transient effects of light and atmosphere, portraying scenes at a specific moment in time. Their paintings reflect the shifting conditions of nature and the changing moods of their surroundings.

This pursuit often led them to depict subjects under different lighting, such as sunrise, sunset, or varying times of day, revealing how light could transform the look and feeling of a scene. Through this focus, Impressionism conveyed the beauty of life’s impermanence and the immediacy of the present moment.

Embrace of Modern Life

Impressionism is defined by its embrace of modern life. Unlike academic traditions that focused on historical or mythological themes, Impressionist artists drew inspiration from the world around them. Their paintings captured the essence of contemporary society, celebrating the ordinary as worthy of art.

Subjects ranged from landscapes and urban scenes to moments of leisure and everyday activity. Streets, cafés, parks, and riversides became favorite settings, reflecting the rhythms of modern Paris. Through vibrant strokes of color and light, the Impressionists conveyed themes of leisure, urbanization, and humanity’s connection with nature. This focus on daily life not only mirrored the changes of their era but also infused their canvases with vitality, preserving fleeting moments of modernity for generations to come.

Color in Impressionism

Color played a revolutionary role in Impressionism, transforming how artists understood its relationship with light. Instead of the muted tones favored in academic painting, Impressionist artists embraced bright, unblended hues to express mood, atmosphere, and the shifting effects of nature.

They observed that colors change constantly under different lighting conditions. To capture this, they applied small, separate strokes of pure color side by side. When viewed from a distance, the eye naturally blended these strokes, creating vibrant, shimmering effects.

The Impressionists also broke with tradition in their treatment of shadows. Rather than relying on black or gray, they used complementary colors to suggest depth and dimension. Advances in synthetic pigments further expanded their palette, enabling bolder and more luminous effects. By layering fresh paint onto damp surfaces, they produced subtle blurs and optical mixing that gave their canvases a sense of immediacy and depth.

Lack of Detail

The absence of intricate detail is a defining feature of Impressionism, marking a clear break from earlier traditions that prized meticulous precision. Instead of focusing on fine details, Impressionist artists aimed to capture the overall impression of a scene through loose brushwork, vibrant color, and the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere.

Impressionist Masters: Famous Artists and Their Paintings

Claude Monet (1840–1926)

Claude Monet is often regarded as the quintessential Impressionist painter, known for his series that explored how light and atmosphere transform familiar subjects. A central figure in the Impressionist movement, he helped reshape French art in the late nineteenth century and laid the groundwork for twentieth-century modernism. His long career was dedicated to capturing landscapes, urban scenes, and the leisure of modern life, from the gardens of Paris to the coast of Normandy.

In his early years, Monet struggled for recognition. While a few of his seascapes, portraits, and landscapes were accepted at the official Salons of the 1860s, several of his more ambitious works, including Women in the Garden (1866, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), were rejected. These setbacks led Monet to join forces with artists such as Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. Together, they organized the first independent exhibition in 1874.

Among the works he exhibited was Impression, Sunrise, a painting whose loose brushwork and unfinished look drew sharp criticism. Reviewer Louis Leroy used the word “impression” mockingly in his critique, yet the artists adopted the label themselves. What began as an insult became the proud name of the movement, Impressionism.

Claude Monet, Woman with a Parasol - Madame Monet and Her Son, 1875.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir was a French painter closely linked to the Impressionist movement in its early years. His paintings captured everyday life with radiant light and vibrant color, creating scenes that felt spontaneous and alive. By the mid-1880s, however, Renoir began to move away from pure Impressionism. He adopted a more structured, classical approach, especially in his portraits and figure paintings, often focusing on women.

Renoir’s art is defined by warmth, joy, and a celebration of life. His subjects ranged from intimate glimpses of daily routines to elegant portraits and sunlit landscapes. Among his most famous works are Luncheon of the Boating Party and Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette, both of which showcase his mastery in depicting leisure, movement, and human connection with luminous beauty.

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Luncheon of the Boating Party, 1881.

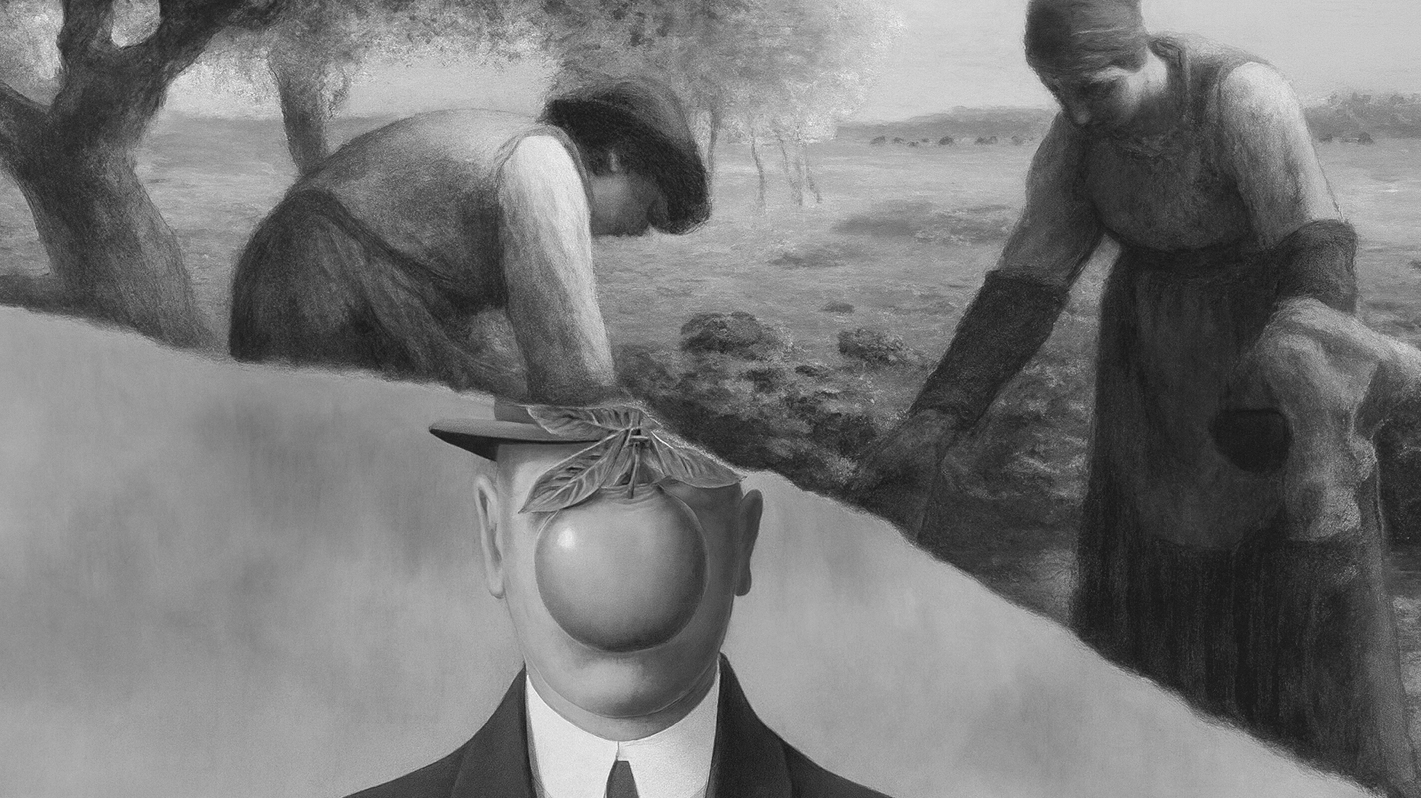

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

Edgar Degas never fully embraced the label of “Impressionist,” preferring to call himself a Realist or Independent. Even so, he played a pivotal role in the movement as a founder, organizer of exhibitions, and central member of the group. Like the Impressionists, Degas sought to capture fleeting moments of modern life. Yet his focus diverged from outdoor landscapes, turning instead to theaters and cafés illuminated by artificial light. He used this light to highlight the contours of his figures, drawing on his strong academic training.

Although he shared the Impressionists’ fascination with contemporary subjects, Degas often chose Parisian dance halls, cabarets, racetracks, opera houses, and ballet stages as his settings. He once remarked to his fellow landscape painters, “You need natural life; I, artificial life.” What fascinated him most was rhythm and movement—racehorses in motion and ballet dancers in rehearsal—not spontaneous gestures but disciplined, rehearsed ones. At the same time, he carefully observed the ordinary motions of working women such as milliners, dressmakers, and laundresses, finding beauty in their purposeful, everyday gestures.

Edgar Degas, The Absinthe Drinker or Glass of Absinthe, 1875-1876.

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895)

Berthe Morisot was a leading French Impressionist painter whose work made a lasting impact on the movement. Her style was marked by delicate brushwork, fluid compositions, and a remarkable sensitivity to light and color. With her innovative approach to atmosphere and form, she helped define the distinctive aesthetic of Impressionism.

Morisot maintained close ties with fellow Impressionists, including Édouard Manet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. In 1894, the critic Gustave Geffroy praised her as one of the “les trois grandes dames” (the three great ladies) of Impressionism, alongside Marie Bracquemond and Mary Cassatt. Despite the challenges faced by women artists in the 19th century, Morisot built a remarkable career and left a legacy as a trailblazer whose contributions were essential to the growth of Impressionism.

Berthe Morisot, Woman at Her Toilette, 1875/80.

Impressionism vs. Post-Impressionism: What’s the Difference?

Impressionism and Post-Impressionism are two of the most influential movements in art history. While they share a common origin, their goals and techniques soon diverged. Impressionist painters sought to capture the fleeting beauty of everyday life, focusing on light, movement, and scenes of modern society.

Post-Impressionist artists, however, moved beyond direct observation. Instead of simply recording the external world, they explored deeper emotions, symbolic meanings, and personal expression. Their work marked a shift from capturing reality as it appeared to interpreting reality through the artist’s inner vision.

Read More Art Articles:

• 6 Forgotten Modern Art Movements You Should Know

• What is Modern Art? Definition, Movements, and Key Characteristics

• Impressionism vs. Post-Impressionism: What’s the Difference?

• 6 Key Art Movements That Came Before Modern Art

↪ Follow us for more updates: YouTube | Instagram