When you hear the word "minimalism," what comes to mind? Maybe a modern, minimalist interior with white walls and clean lines. But Japanese minimalism is different.

Unlike Western minimalism, which often emphasizes decluttering and functionality, Japanese minimalism embraces imperfection (Wabi Sabi), nature, and negative space (Ma). It is not just a design trend—it is a philosophy and a way of seeing the world.

Whether you're drawn to minimalist design, traditional Japanese aesthetics, or a mindful way of living, this guide will help you understand the essence of Japanese minimalism and how it shapes everyday life.

The Philosophy of Japanese Minimalism

To truly understand Japanese minimalism, we must look beyond design and explore its philosophical roots. Japanese minimalism is not just a style—it is shaped by centuries of philosophy, art, and a way of life that values simplicity, balance, and a deep connection with nature.

One of the core influences on Japanese minimalism is Zen Buddhism, which emphasizes simplicity, mindfulness, and the power of emptiness.

In Zen thought, emptiness is not just the absence of things—it is a space that allows for clarity, focus, and meaning. It encourages us to remove distractions, quiet the mind, and fully appreciate what remains.

This concept is best expressed through Kū (空), often translated as "emptiness." But in Japanese aesthetics, emptiness is not a void—it is an open, boundless space full of possibility.

We see this reflected in traditional Japanese tatami rooms. At first glance, they may appear empty—just a wooden floor, sliding Shoji doors, and soft natural light.

But this intentional emptiness allows for adaptability. A tatami room can serve as a living space during the day, a place for tea, or a sleeping area at night. Its openness creates flexibility and potential—this is the essence of Kū.

Another key concept is Mu (無), meaning "nothingness" or "letting go." While Kū represents open space, Mu is about removing what is unnecessary. It teaches us that by letting go of excess, we free ourselves from distraction and find clarity.

This is why Japanese rock gardens are so simple. Instead of filling the space with flowers and ornaments, they use only a few rocks, sand, and open space. The absence of excess draws attention to each element, allowing the mind to slow down, focus, and find stillness in simplicity.

Together, Kū and Mu shape Japanese minimalism. They remind us that less is not emptiness—it is space for meaning.

Japanese minimalism is not just about aesthetics—it is a way of seeing, living, and experiencing the world. It embraces simplicity, stillness, and deep awareness of the present moment.

But Kū and Mu are not the only ideas that define Japanese minimalism. They exist alongside other key concepts, such as Ma (間), which focuses on the space between things, and Wabi Sabi (侘寂), the appreciation of imperfection and impermanence. These philosophies work together, shaping a way of living that values simplicity, depth, and harmony with nature.

Japanese Minimalist Design: The Beauty of Simplicity and Natural Materials

Understanding the philosophy of Japanese minimalism is one thing, but how does it

actually shape everyday life?

One of the best examples can be seen in Japanese architecture and interior design. Unlike many modern homes—often filled with furniture, decorations, and personal items—Japanese minimalism takes the opposite approach. Instead of focusing on what can be added, it emphasizes what is left out.

Every element in a Japanese minimalist space is carefully considered. The materials, layout, and even the empty spaces all play a role in creating harmony and tranquility. Despite its simplicity, Japanese minimalism never feels cold or uninviting. Why is that?

Photo Credit: ArchDaily | Architects: Aterier Salt, Koyori | Photographer: Junichi Usui.

One key reason is its use of natural materials, which bring warmth, simplicity, and a deep connection to nature. Instead of synthetic or artificial materials, Japanese interiors feature wood, paper, and tatami, creating an organic and timeless aesthetic.

.Wood is used for floors, walls, and structural elements, often in light tones like cedar or cypress, enhancing the feeling of openness.

.Shoji sliding doors, made of wooden frames and translucent paper, allow soft, diffused light to enter, creating a peaceful atmosphere.

.Tatami mats, woven from rush grass, add texture and carry a subtle, earthy scent, further strengthening the connection to nature.

But these materials are not chosen just for their beauty—they are valued for their ability to age gracefully and blend naturally into their surroundings. Their organic textures and muted tones create the calm, balanced atmosphere that defines Japanese minimalist spaces.

Japanese Minimalism in Art: Simplicity, Imperfection, and the Mono-ha Movement

Japanese minimalism is not just about architecture and interior design—it also extends into art.

Traditional Japanese crafts like ceramics, lacquerware, and Kintsugi embody minimalist principles. A simple tea bowl may have an uneven shape or a rough texture, but its beauty lies in imperfection and simplicity. Rather than relying on flashy decorations, these objects invite the user to appreciate the material, the form, and the experience of holding them.

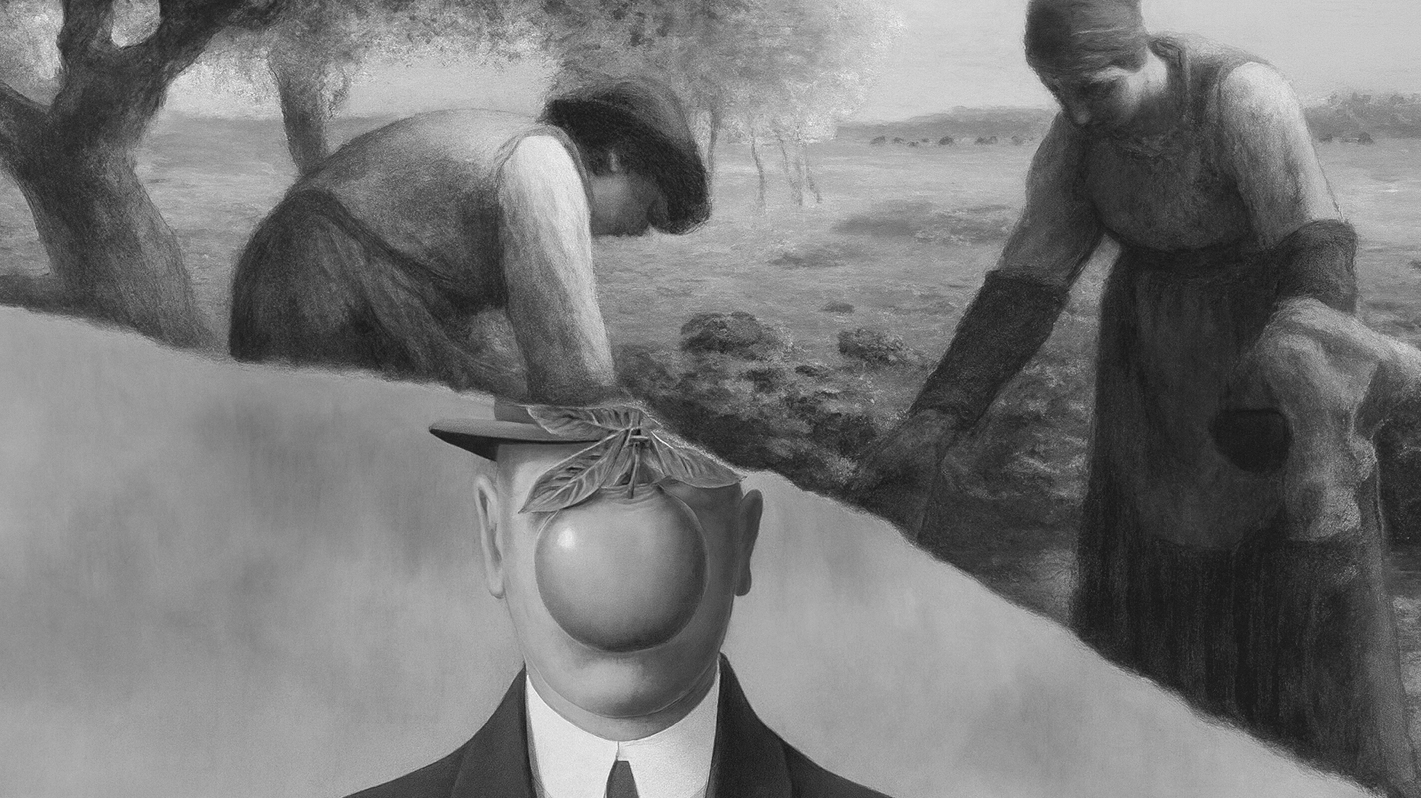

Minimalism in Japanese art, however, is not limited to traditional forms. In the late 1960s, a contemporary art movement called Mono-ha (もの派), or the "School of Things," emerged. Unlike Western minimalism, which often emphasizes geometric shapes, industrial precision, and repetition, Mono-ha focused on the raw state of materials and their relationship with space.

Katsuro Yoshida, Cut-off (Paper Weight), 1969.

Mono-ha artists rejected commercialism and questioned modern industrialization. Inspired by Zen philosophy and its emphasis on emptiness and impermanence, they worked with natural and industrial materials—stone, wood, glass, and metal—without significantly altering them. Instead of imposing meaning, their goal was to let the materials exist as they are, encouraging viewers to engage with them on a deeper, more contemplative level.

While Western Minimalism sought precision and control, Mono-ha embraced imperfection, transience, and the quiet tension between objects and emptiness. This approach reflects a uniquely Japanese interpretation of minimalism—one that values presence, awareness, and the beauty of what is left unsaid.

Japanese Minimalism in Everyday Life: The Art of Living with Intention

Beyond art, the principles of Japanese minimalism are deeply woven into everyday life. It is not just a visual style but a way of thinking—shaping how people live, the objects they choose, and the spaces they create.

In Japan, the concept of Danshari (断捨離) was introduced by author Hideko Yamashita. But Danshari is more than just decluttering—it is about making intentional choices. It encourages people to keep only what is truly necessary and meaningful, creating a space that reflects personal values.

Yamashita explains that Danshari is about listening to your inner voice. Instead of holding onto things out of habit or obligation, she encourages people to ask themselves: How do I truly want to use this item? Do I really need to keep it? Rather than following external pressures, Danshari helps people make mindful decisions based on their own values, creating a way of living that feels authentic.

She also notes that when you break free from clutter and your space becomes more organized, your natural sense of aesthetics awakens. Decluttering is not just about tidying up—it is about envisioning the space you truly want to live in and creating it with intention.

Japanese minimalism is not about restriction—it is about freedom. By removing what is unnecessary, we make space for what truly matters.

Whether in architecture, art, or daily life, this philosophy teaches that simplicity is not emptiness. It is an invitation to live with greater awareness, presence, and appreciation.

Perhaps that is why Japanese minimalism continues to inspire people around the world. It is not just a design trend but a way of seeing and experiencing life itself.

Read More Design Articles:

• Kintsugi: Finding Beauty in the Art of Repair

• Ikebana: The Art of Japanese Flower Arrangements

• What is Wabi Sabi? Embracing the Beauty of Imperfection

• Ma: The Japanese Aesthetic of Negative Space and Time

About Us

Dans Le Gris is a brand that began with everyday jewelry, with each handmade piece designed and crafted in Taiwan. We deeply value every detail, dedicating ourselves to creating timeless pieces through collaboration with experienced craftsmen.

In our journal, we provide irregular updates featuring articles about art, culture, and design. Our curated content encompasses diverse aspects of life, with the aspiration to offer meaningful insights and inspiration.