In many cultures, empty space is often viewed as something incomplete—a blank wall waiting to be filled, a silent pause that feels uneasy, or a page that demands words.

In Japanese aesthetics, however, emptiness is not a void to be corrected but a presence to be felt. Space can hold silence, evoke emotion, and reveal what cannot be seen.

This article explores the Japanese concepts of Ma (間), Yohaku no Bi (余白の美), and the art of subtraction—ideas that shape how Japan perceives and designs space. By understanding these principles, you may begin to see space not as absence, but as a form of beauty in itself.

Kū (空): The Buddhist Concept of Emptiness in Japanese Aesthetics

To understand why space holds such deep meaning in Japanese aesthetics, we must begin with an ancient concept known as Kū (空).

In Buddhism, Kū is often translated as “emptiness,” yet it does not mean nothingness or despair. It expresses the understanding that all things are impermanent, interconnected, and without an independent self. In both art and life, empty space becomes a visual expression of this truth, not a void, but a gentle reminder that everything exists only in relation to everything else.

Imagine a flower. It cannot bloom alone. It depends on soil, sunlight, water, air, and even pollinators. Remove just one condition, and the flower ceases to exist. This interdependence lies at the heart of Kū.

Japan’s native tradition, Shinto, adds another dimension. Rooted in animism, it finds divinity in all things, from mountains and rivers to stones, trees, and even the spaces in between. An empty courtyard, a quiet forest clearing, or the threshold beneath a torii gate can all become places where the sacred is felt.

Beyond religion, Japanese culture has long cherished subtlety and suggestion. Silence in conversation or a gesture left unfinished can convey more meaning than words themselves. Aesthetics like Ma (間) and Yohaku no Bi (余白の美) reflect this sensibility, showing that what is left unseen or unsaid can often be the most profound expression of all.

Ma (間): The Japanese Aesthetic of Space and the Pause Between Things

From this foundation, Japanese ways of seeing space took shape, influencing everything from daily life to art, architecture, and design. Among these ideas, perhaps the most essential is Ma (間).

If Kū is the philosophy of emptiness, Ma (間) is how that emptiness is felt and lived. It is the interval, the pause, the space in between.

We experience Ma (間) when we sense the vastness of the sky, not simply because it is blue, but because of the open space between the clouds. This space is not empty; it is what gives the sky its depth and vitality.

We also perceive Ma (間) in music, within the silence that shapes each note. Even in conversation, a quiet pause between words is not awkward. It is Ma (間), the space that allows for listening, reflection, and respect.

Ultimately, Ma (間) is the art of perceiving the space between. It gives rhythm to movement, harmony to sound, and meaning to form. In Japanese aesthetics, this awareness of in-between space turns emptiness into presence.

Yohaku no Bi (余白の美): The Beauty of Empty Space in Japanese Aesthetics

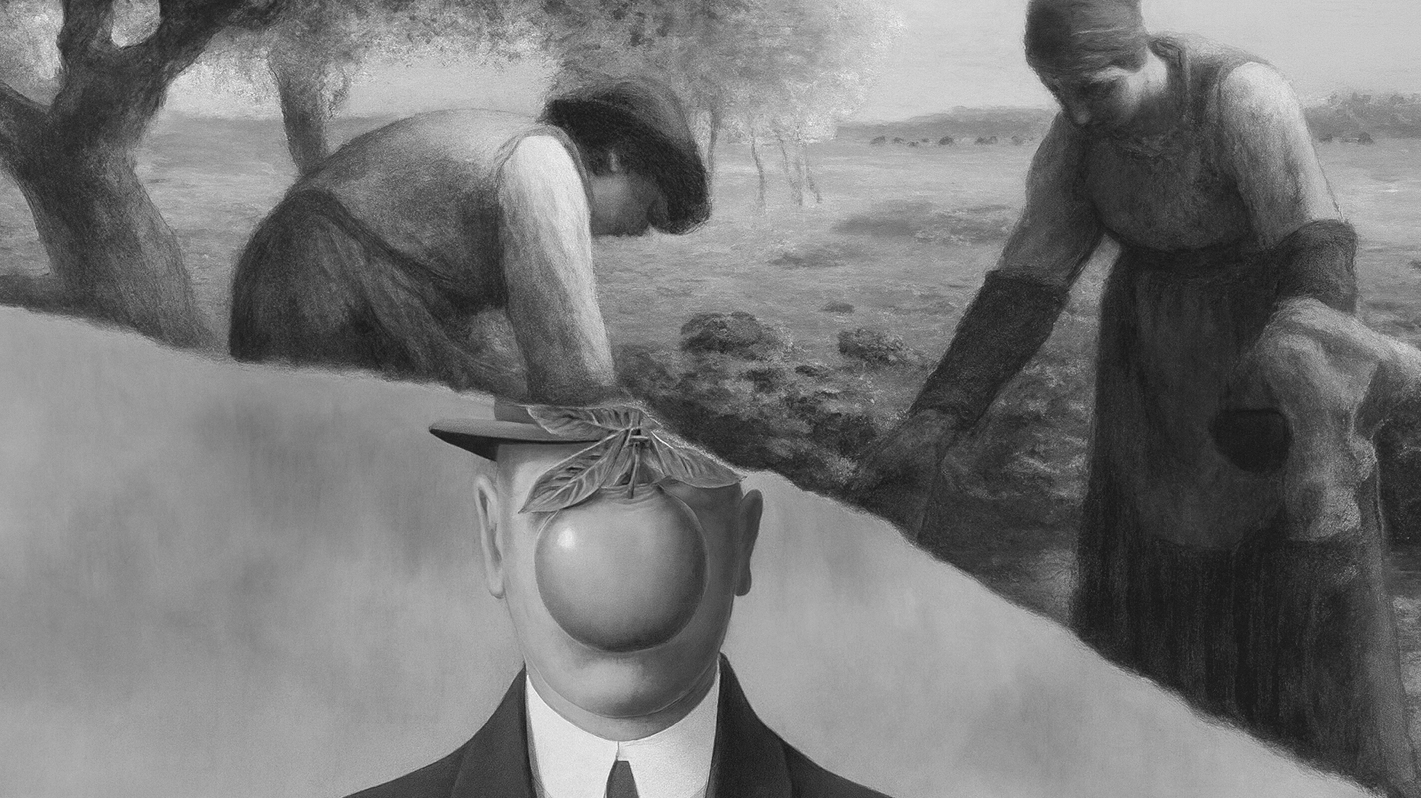

If Ma (間) shows how pauses and intervals give form to experience, Yohaku no Bi reveals the beauty of empty space.

Yohaku no Bi is often compared to what we call “negative space” in English. While they share a similar idea, they are not quite the same. In Western design, negative space often serves as background, supporting the main subject. Yohaku, however, celebrates the blankness itself, the margin left intentionally unfilled, where form and emptiness exist in mutual balance.

Rooted in the broader concept of Ma (間), Yohaku no Bi treats empty space as a living presence. While Ma (間) can refer to both time and space, Yohaku no Bi is almost always visual, especially in Japanese art and design. Here, emptiness is not secondary; it is an essential part of the composition, as meaningful as the subject itself.

Photo by Heather Newsom on Unsplash

One of the most striking expressions of Yohaku is the use of white. Japanese designer Kenya Hara describes white as carrying infinite potential. He writes, “White exists on the periphery of life. Bleached bones connect us to death, but the white of milk and eggs speaks to us of life.” Seen in this way, white in Japan is not merely the absence of color but a space that invites openness, reflection, and new beginnings.

From a physical perspective, white reflects every wavelength of light, yet to the eye it often appears as nothing at all. This paradox makes white both presence and absence, a color that feels like emptiness. But this emptiness is not void; it suggests a place where something is about to emerge.

Think of a blank sheet of paper. Its emptiness stirs the desire to write, to draw, to create. It becomes a vessel that holds potential and invites expression.

Unlike Ma (間), which emphasizes the interval or pause between things, Yohaku no Bi celebrates the beauty of blankness itself. It invites the viewer’s imagination to complete what is left unseen. In a culture that values subtlety and restraint, Yohaku no Bi teaches that what is absent can be just as expressive as what is present.

Hikizan no Bigaku (引き算の美学): The Japanese Aesthetics of Subtraction

A third way Japan approaches space is through Hikizan no Bigaku, the aesthetics of subtraction.

While Yohaku no Bi values leaving space unfilled, Hikizan no Bigaku is about intentionally removing what is unnecessary so that only what truly matters remains. It is design through reduction, creating harmony by taking away rather than adding more.

This principle is deeply embedded in traditional Japanese architecture. A tea room, for instance, is stripped of decoration so that the mind can focus on the simple act of sharing tea. The tokonoma, or alcove, holds just one scroll or a single flower arrangement, allowing it to speak with quiet strength and dignity.

The same sensibility appears in Japanese gardens, especially the dry landscape (karesansui) style. To express the vastness of the sea, actual water is not used. Instead, it is removed, and in its place, sand and stones are arranged. Stones become islands, sand becomes waves, and the viewer’s imagination completes the scene.

Photo by Fabrizio Chiagano on Unsplash

By removing rather than adding, Japanese aesthetics invite us to look beyond appearances. The visible world is seen as temporary, a surface that conceals a deeper reality. Life itself is fleeting, a passing form rather than a permanent substance.

This reflects a cultural value that places spirituality above materiality. Japanese art often asks the viewer to perceive what is not shown. To see what is present is ordinary; to sense what is absent is refinement, elegance, and culture itself.

Attention is therefore given not to the surface but to what lies behind, not to the obvious but to the hidden depth. It reminds us not to be confined by what the five senses perceive, but to sense the truth that lies beyond them.

Even in modern Japanese design, subtraction continues to shape global aesthetics. From Muji’s minimalist objects to contemporary product design, the power often lies not in what is added but in what is omitted. Muji’s philosophy embodies emptiness and anti-branding, removing logos, decoration, and excess so that each product speaks through function, simplicity, and quiet integration into daily life.

Unlike Yohaku no Bi, which celebrates the beauty of blankness, Hikizan no Bigaku emphasizes intentional reduction. It is the discipline of knowing what to remove, creating beauty through restraint and awareness.

In a world that often celebrates abundance and excess, the aesthetics of subtraction remind us that simplicity reveals depth, and that absence can be the strongest form of presence.

The Beauty of Emptiness: What Japanese Aesthetics Teach Us About Space

Through Kū, Ma (間), Yohaku no Bi, and Hikizan no Bigaku, we begin to understand why space holds such deep meaning in Japanese aesthetics. In emptiness lie the greatest possibilities. A pause, a blank margin, or a deliberate act of subtraction is never meaningless; each carries presence, energy, and potential.

In a world that often fears emptiness and rushes to fill every gap, Japanese aesthetics remind us that space itself can hold beauty and meaning. To leave something open is not to leave it unfinished. It is to invite imagination, to honor silence, and to allow depth to emerge.

Perhaps this is the quiet lesson. What is absent can be just as powerful as what is present, and in learning to see space differently, we may also learn to see life itself with new eyes.

Read More Design Articles:

• Negative Space in Art, Design, and Photography: Definition, Meaning, and Examples

• Ma: The Japanese Aesthetic of Negative Space and Time

• 7 Japanese Zen Aesthetic Principles That Define Wabi Sabi

• The Secret Meaning Behind Japanese Summer Colors