In our previous article, "6 Female Artists Who Changed the History of Art Forever," we mentioned how the spotlight in art history has often been directed toward men, even though many women have powerfully and permanently shaped the course of art.

In today’s article, we highlight six more female artists who helped define art history in their own right. From Impressionist salons to conceptual installations, their names might not appear in every textbook, but their influence is undeniable. These overlooked women artists deserve to be remembered, studied, and celebrated.

Berthe Morisot: The Feminine Eye of Impressionism

We begin with Berthe Morisot, born in 1841 in Paris. She was a painter whose name you might not hear as often, even though she helped shape one of the most influential art movements in history.

Morisot was one of the founding members of the Impressionist movement and the only woman in the original group. In 1874, when a circle of artists broke away from the official Salon to hold their own independent exhibition, she was among them. She went on to exhibit in seven of the eight Impressionist shows, more than Monet himself.

But Morisot’s world looked different. While many of her male peers painted bustling city streets or sweeping landscapes, she turned her attention inward, toward quiet interiors, family life, and intimate daily moments. Not because she lacked imagination, but because the public world was often closed off to women at the time.

These boundaries did not limit her art. They shaped it. Her brushwork was delicate yet confident. Her colors glowed with light. There is a softness in her paintings, but never passivity. Only a deep, thoughtful understanding of presence and time.

In her lifetime, critics often described her work as “feminine” or “intimate,” words that, back then, were used to diminish rather than praise. Today, we understand them differently.

Morisot did not resist the world she lived in. She transformed it. She turned domestic life into something poetic and meaningful. Her painting The Cradle, for example, shows a woman watching over a sleeping infant. It is a quiet moment, yet filled with tenderness, atmosphere, and a gentle awareness of time.

In her hands, the everyday became luminous. Through presence, sensitivity, and the subtle play of light, Morisot revealed the beauty within the quietest moments of life.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp: The Woman Who Made Geometry Dance

Sophie Taeuber-Arp was born in 1889 in Switzerland and remains one of the most versatile and visionary artists of the twentieth century.

Long before Kandinsky gained fame for abstract compositions, she was embroidering geometric patterns by hand. In 1918, she designed puppets that looked strikingly modern, part robot and part toy. She believed that beauty should live in the objects we use every day.

A painter, dancer, sculptor, textile designer, and teacher, her creativity moved freely between disciplines. Where others saw boundaries, she saw possibilities. She pursued a single goal: to make beautiful things with clarity and precision.

While many artists chose a single medium, she embraced them all.

She made embroideries and paintings, carved sculptures, edited magazines, created puppets, and constructed enigmatic Dada objects.

Taeuber-Arp began exploring geometric abstraction as early as 1915, long before it was widely accepted in Europe. She merged traditional crafts with modernist abstraction, challenging the divide between art and design. Her works often featured circles, squares, and rhythmic lines, not as decoration but as living forms. These appeared in textiles, marionettes, interiors, and everyday objects.

In her hands, abstraction became playful, precise, and deeply human.

While the Dada movement in Zurich embraced chaos and absurdity, Taeuber-Arp brought something different, a sense of structure, clarity, and calm. She was one of the few women at the center of Dada, and her presence introduced a new kind of energy that combined logic with imagination.

Later in her career, she worked alongside her husband Jean Arp and helped shape the language of modern abstraction. Although often overshadowed by his name, she maintained a distinct and independent voice.

Today, she is recognized not only as a brilliant artist but as a pioneer of modern design. She was someone who did not just create shapes but gave them life. Someone who made geometry feel human.

She died unexpectedly in 1943 at the age of 53, but her influence continues to grow.

In a world that once separated art from daily life, Sophie Taeuber-Arp brought them back together, one circle, one stitch, one step at a time.

Lee Krasner: A Pioneer in Her Own Right

Speaking of Abstract Expressionism, you’ve probably heard of Jackson Pollock. But what about Lee Krasner?

Krasner was born in 1908 in Brooklyn, New York, and became one of the fiercest and most inventive voices in American Abstract Expressionism. Yet for much of her life, she was known not for her own work but for being Jackson Pollock’s wife.

What often gets overlooked is that Krasner was already an established artist before she ever met him. She studied at Cooper Union, the National Academy of Design, and later trained with the influential German-born abstract painter Hans Hofmann.

Her foundation was strong. She understood classical drawing, Cubist structure, and modernist experimentation. But she was never content to repeat herself. Throughout her career, she pushed constantly against limitation.

In the 1950s, she began creating powerful collages. She cut apart earlier drawings and paintings, then reassembled the fragments into raw, striking compositions. It was an act of reinvention, a refusal to remain fixed in any one identity or phase of work.

After Pollock’s death in a car crash in 1956, Krasner moved into his barn studio in East Hampton. There, she began working on a much larger scale.

One key painting from this period, part of what became known as her Earth Green series, features sweeping black brushstrokes layered with swaths of pink, soft off-whites, and deep green. The forms suggest the female body and botanical life, organic shapes tied to cycles of growth, transformation, and grief.

Loss did not silence her creativity. It deepened it.

Krasner once said, “I was a woman, Jewish, a widow, a damn good painter. I had to prove all of them.”

Today, we see her not as an artist in someone else’s shadow but as a major figure in postwar American art. She remained committed to experimentation, constantly shifting in technique, approach, and scale. Her persistence left a path of courage and possibility for generations of women artists.

Leonora Carrington: The Surrealist Who Refused to Be a Muse

Leonora Carrington was born in England in 1917 into a wealthy but rigid family. They expected her to become a proper lady. She chose something else: wildness over obedience, freedom over formality.

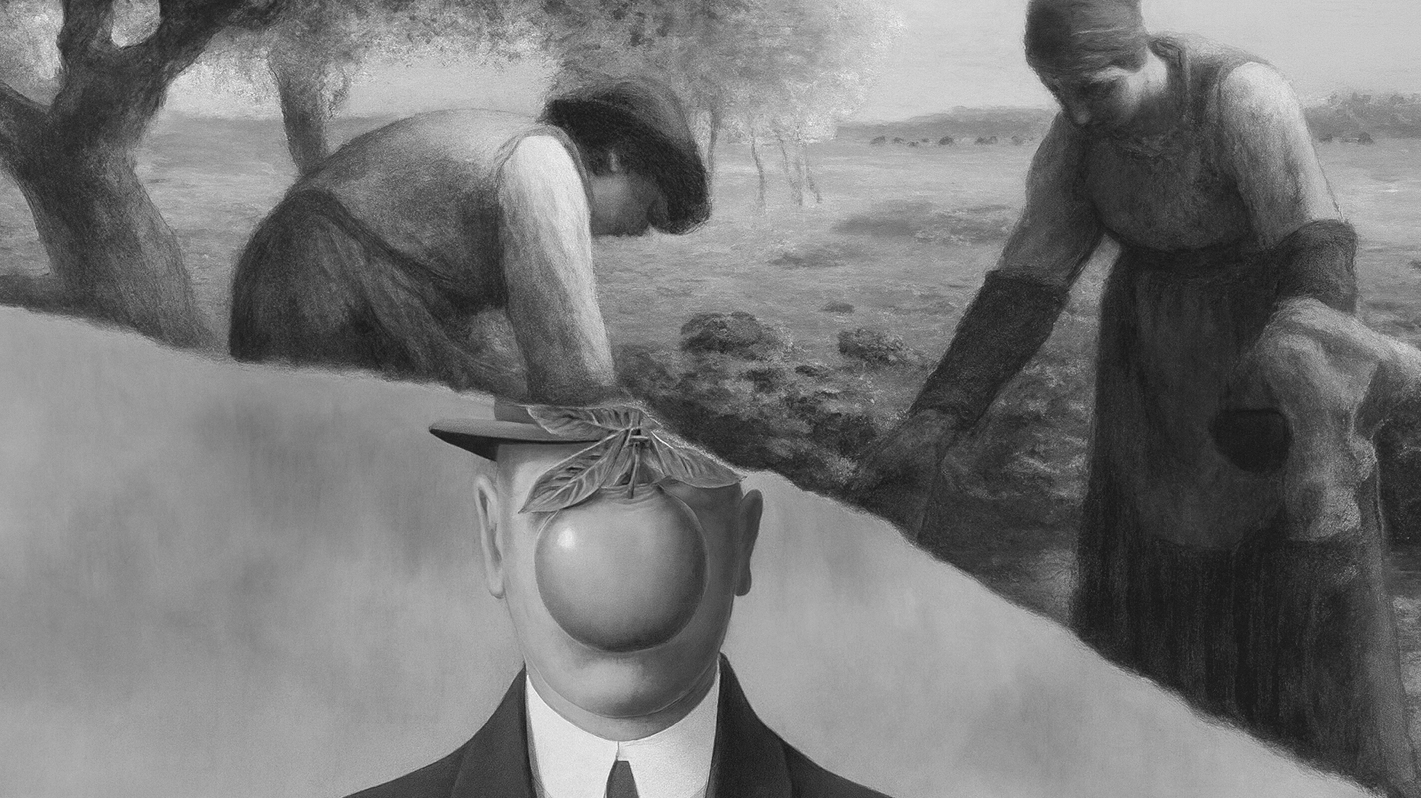

By her early twenties, she had run away with the German Surrealist Max Ernst and entered the heart of Europe’s avant-garde. But Surrealism’s view of women was complicated.

Many male artists embraced Freudian ideas that cast the female psyche as mysterious and intuitive, romanticized but rarely respected. Women were often seen as muses, not creators.

Carrington refused that role. As she once said, “I didn’t have time to be anybody’s muse. I was too busy rebelling against my parents and learning to be an artist.”

Her paintings stood apart. They featured strange creatures, ghostly figures, and women engaged in magical rituals. Carrington built a symbolic world rooted in transformation and the sacred, not tied to any single religion but alive in the quiet corners of the mind.

After the outbreak of World War II and a period of personal upheaval, Carrington fled to Mexico City, where she would live for the rest of her life. There, she found creative freedom and community. Together with Remedios Varo and Kati Horna, she helped shape a rare circle of women Surrealists who forged their own path.

Her work became even more layered and symbolic. She painted hybrid bodies, enchanted spaces, and women as figures of strength and mystery. She believed in invisible forces, and her canvases shimmered with presence.

In her 1943 drawing Kitchen Clock, she imagined the kitchen not just as a domestic space but as a site of transformation, where women perform everyday alchemy. This small, intimate work reflected a Surrealism expanding beyond Paris and beyond male-dominated narratives.

Today, Carrington is remembered not only as a Surrealist but as a visionary who redefined the subconscious on her own terms. She never explained her visions. She simply invited us in.

Chiharu Shiota: Weaving Memory into Space

Let’s turn to Chiharu Shiota, a Japanese artist known for her powerful performances and installations that give form to intangible experiences such as memory, anxiety, dreams, and silence.

Born in Osaka in 1972, Shiota originally trained as a painter. But early in her career, she felt that paint was not enough. She wanted her work to occupy space, to surround people, and to live in the body as much as in the eye.

She is best known for her immersive thread installations. Black, red, or white strands stretch across rooms like tangled webs, wrapping around everyday objects such as keys, suitcases, shoes, or hospital beds. The effect is haunting and deeply personal, as if memory itself has taken shape and filled the room.

In East Asian cultures, red thread often symbolizes fate or human connection. Shiota uses it to explore absence, longing, and the invisible ties between people. Her installations do not depict memory. They allow us to move through it.

Much of her art is shaped by personal experience. As a student in Germany, she struggled with identity and the feeling of being far from home. Later, a serious illness led her to reflect on life, death, and what remains after we are gone.

Her installations blur the line between dreams and memory. Their silence invites reflection, while their scale evokes awe.

One is reminded of the story from the Chinese philosopher Zhuangzi, in which a man dreams he is a butterfly, then wonders if he is now a butterfly dreaming he is a man. That same uncertainty appears in her 2018 work Butterfly Dream.

Shiota’s process is physical. She and her team spend days or weeks weaving thousands of strands by hand. There is labor in it, stillness too, and something close to ritual.

She once said, “Memory is something we cannot touch or see, but it is very strong.”

Like memory, her work is quiet but lingers. It invites us to pause, to breathe, and to feel what cannot be spoken.

Yoko Ono: A Pioneer of Conceptual and Participatory Art

We end with Yoko Ono, a Japanese artist, musician, and activist who has challenged the way we define art for more than half a century.

Born in Tokyo in 1933, Ono moved to the United States in the 1950s and became a key figure in New York’s avant-garde scene. She was one of the few women closely involved with the Fluxus movement, which rejected traditional art objects in favor of ideas, actions, and experiences.

Ono’s early work blurred the line between art and life. Many of her first pieces were based on instructions, shared verbally or in writing. In Painting to Be Stepped On, she placed a canvas on the floor and invited people to walk across it, either physically or in their minds. It was a quiet but radical gesture that dismantled the divide between art and the everyday.

Her work is not about making objects. It is about inviting people to imagine, to participate, and to become part of the piece itself. In Cut Piece, she sat silently on stage as audience members cut away pieces of her clothing. The act was simple but deeply provocative. It raised urgent questions about vulnerability, power, and how women’s bodies are viewed.

Throughout her career, Ono has used simple materials to explore complex ideas: peace, grief, feminism, intimacy, and connection. In Wish Tree, a series she began in the 1990s, visitors write their wishes on paper and tie them to tree branches. Each note becomes part of a growing field of shared hope.

Although she is often remembered for her relationship with John Lennon, Ono’s artistic legacy stands entirely on its own. Long before and long after that chapter, she made work that questioned systems, broke boundaries, and opened emotional space.

Her practice evolved alongside artists like John Cage and Nam June Paik, who believed art did not have to live in a gallery. It could be an idea, a sound, a thought exchanged between strangers.

Her work is conceptual but never cold. It asks you to look inward. To listen. To imagine a different way of being.

As Yoko Ono once said, “A dream you dream alone may be a dream, but a dream two people dream together is reality.”

Her work invites us to share that dream, to become not just viewers but participants in something larger than ourselves.

Read More Art Articles

• 6 Forgotten Modern Art Movements You Should Know

• Surrealism in Art: From the Unconscious Dream to Artistic Reality

• Contemporary Art Meaning: Why It Matters in Today's World?

• Impressionism: The Art of Capturing Fleeting Moments

↪ Follow us for more updates: YouTube | Instagram